Information leakage from hidden layer activations of neural networks

26 Jul 2019(cross-posted from my Medium blog)

Problem Definition:

Consider this scenario: You have an app on your phone that assures you that your user data collected by it will not leave the device as-is. The app uses a neural network to serve some functionality, taking the user data as input and generating an intermediate representation which is then sent to a server to make the final prediction. What guarantees can we make about user privacy if an adversary gains access to the intermediate representation? Can the intermediate representation be used to glean off personally identifiable and/or sensitive information? More generally, does the neural network learn private(for ex: demographic) attributes about a user that are not relevant to making the prediction at hand? Do changes to the model in order to improve privacy necessarily have to hinder accuracy? Two neatly written papers at EMNLP 2018 provide insight into this issue.

Nuances

Private information in the input can be either explicit or implicit. Explicit private information refers to the words in the input that themselves constitute sensitive content. Implicit private information refers to personally identifiable/sensitive content that can be inferred from the text, such as demographic attributes (gender, race, authorship etc). There are two different issues emanating from private information being leaked in neural representations. From a security standpoint, we can see this as a loss of privacy, but in some cases we can also view this as a problem of undesirable incidental learning, where our predictions rely on protected demographic attributes that might be irrelevant to the problem.

Adversarial attack:

Let the main classifier consist of input x that is passed through a neural network to generate an intermediate representation r(x). The intermediate representation is then used to calculate the final prediction y. Let z be the private information contained in x. Here, z can be represented in many ways, but for the purposes of our discussion let it be a list of indicator variables that indicate the presence or absence of some demographic attribute in the input. The adversary’s aim is to determine z using only r(x) but without access to x.

To achieve this, the adversary learns their own classifier. We assume that they do not have access to the input x but do have access to the representation function r. Thus, the adversary can create any dataset consisting of input-output pairs (r(x), z) and learn to predict z from r(x). If the accuracy of the classifier on new examples is above chance-level, then it means that there has been leakage of personal information to the intermediate representation r(x).

Privacy-preserving representations:

Coavoux et al., propose three different methods to generate privacy-preserving intermediate representations.

Multidetasking using adversarial training: In this setup, an adversarial classifier is trained simultaneously alongside the main classifier. The adversarial classifier effectively simulates a training-time attack. The loss function of the main classifier includes a penalty scaled by how well the adversarial classifier is able to predict the personal information z.

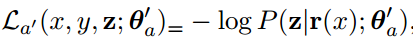

The loss function of the adversarial classifier is:

Which is the usual cross entropy loss.

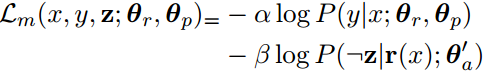

The loss function of the main classifier is:

here 𝝰 and 𝝱 are used to balance the importance of the first and second component respectively. The first component is the usual cross entropy loss while the second component tries to reduce the classification accuracy of the adversarial classifier.

Adversarial generation: In this setup, adversarial training is used to predict the actual text of the training examples instead of the personal information z that can be extracted from it. A benefit of this is that we are no longer restricted to the type of private information that we explicitly represent using z. This comes at the expense of added computational complexity.

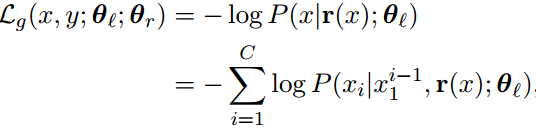

The loss function of the adversarial generator is

Here, xi represents the ith character in the text and C represents the total number of characters.

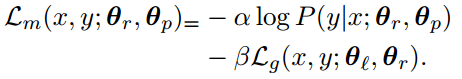

The loss function of the main classifier is:

Declustering: If the adversarial classifier is able to predict private information with high accuracy, it probably means that the intermediate representation has learned to cluster points that have similar z closer to each other in vector space in the generated representation. If this assumption is true, then declustering the representation can possibly help. The loss function of the classifier has a penalty if examples containing similar private information are clustered together in the intermediate representation.

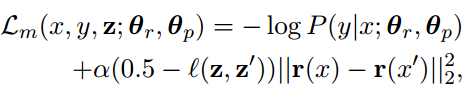

The loss function of this classifier is :

Here, x’, z’ is a random example sampled uniformly from the training set. The authors use the Hamming distance as the similarity measure.

Gradient Reversal Layer:

Elazar et al., use a more efficient form of adversarial training that utilizes a gradient reversal layer. The gradient reversal layer exists between the layer that generates the intermediate representation r(x) and the adversarial layer(s). During the forward pass, the gradient reversal layer just acts as the identity and passes r(x) through it. During the backward pass, it scales the gradients passing through it by some value -p. The negative sign ensures that the main classifier receives the opposite of the gradients that the adversary receives, thus in effect forcing it in a direction opposite to the adversary.

Conclusion:

Are these techniques effective? Elazar et al., demonstrate that these techniques cannot be used to give any guarantees that there is no leakage of private information. Current state-of-the-art adversarial training techniques are not effective in completely preventing private information from leaking to further layers. The only thing we can reliably do is to use these techniques to demonstrate the leakage of private information, but not prove the absence of it. The authors experimented with various network characteristics like capacity, weights, ensembling adversaries etc but it did not help much.

As expected, using these techniques also results in a (slight) drop in accuracy as shown by Coavoux et al.

Differential privacy schemes that add noise to the input look promising. I am looking forward to playing around a bit with that.